Launching a Hedge Fund: A Founder-Friendly Legal Roadmap

Launching a hedge fund (or hedge-fund-like private investment vehicle) is less about picking a brand name and opening a brokerage account — and more about setting up the right legal structure, offering framework, and operating rules before you take outside money. The goal of this guide is to give you a practical, founder-friendly roadmap so you can move fast without creating regulatory or investor-relations problems that surface during fundraising, audits, or a future institutional raise.

This is written for startup founders, emerging fund managers, and business owners who are considering raising capital from outside investors and want a clear picture of what needs to be decided early, what can wait, and where counsel adds the most leverage.

You’ll learn how legal guidance shapes (i) your entity diagram and economics (GP/management company/fund vehicle), (ii) the key exemptions that typically make a private fund possible, and (iii) the core documents investors will expect (PPM, governing agreement, subscription materials, and side letters). For a deeper overview of why legal oversight matters, see what a hedge fund lawyer does (and when to hire one).

Outcome: you’ll walk away with concrete steps, checklists, and decision points you can act on immediately — especially around investor eligibility, offering mechanics, and document readiness.

So what should you do differently? Put the effort into the first-pass structure and compliance choices upfront, instead of “DIY now, fix later.” Most expensive hedge fund legal cleanups happen after money is accepted — when changing entities, exemptions, or disclosures is slow, costly, and credibility-damaging.

Fund Structure, Entities, and Design Decisions

Your fund “structure” is the plumbing that governs who has authority, who bears liability, how fees flow, and how investors come in. Getting it right early saves you from re-papering investors later (often the hardest kind of fix).

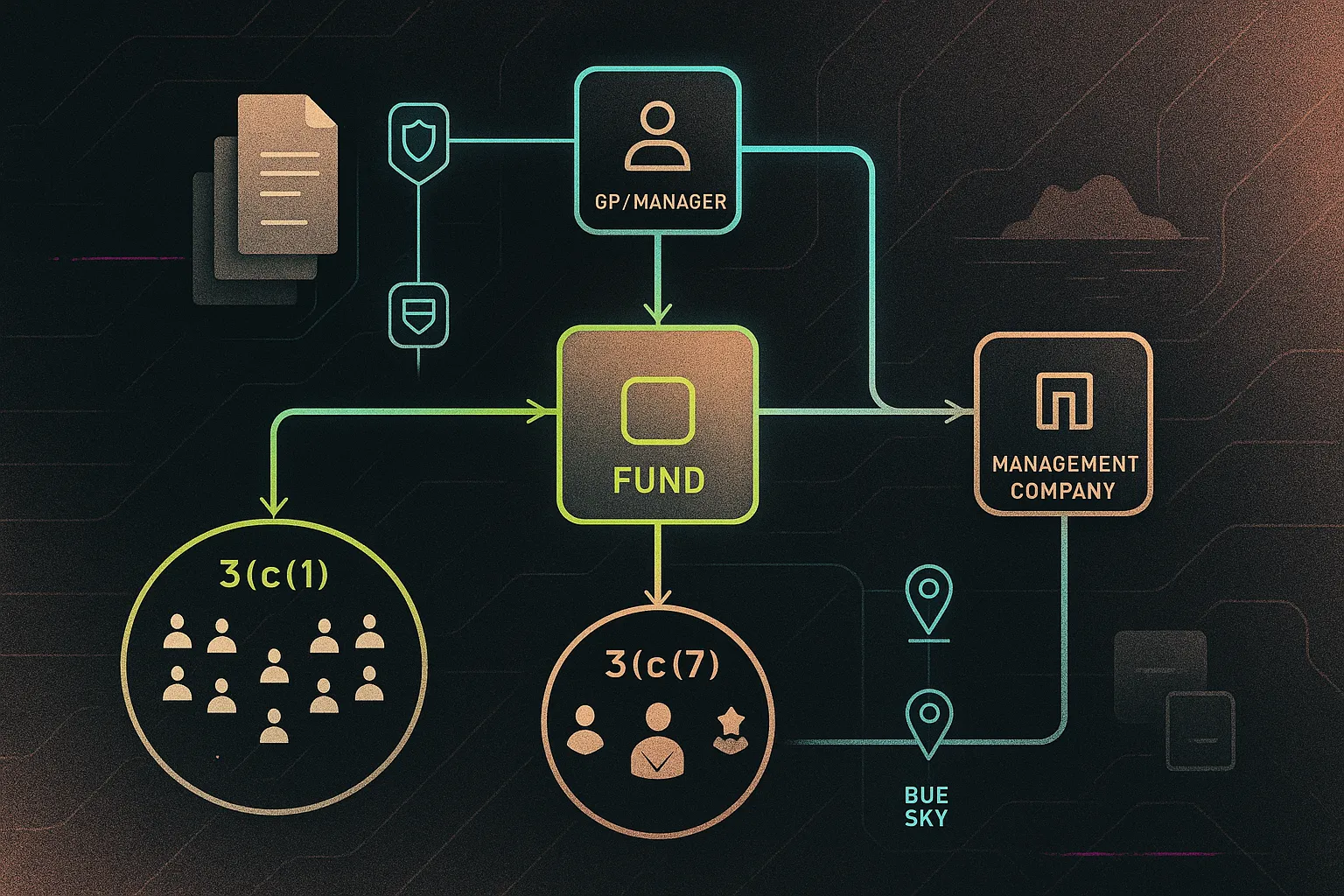

Core entity choices: most U.S. private funds use (1) a fund vehicle (often a Delaware LP or LLC), (2) a GP (for an LP) or managing member (for an LLC) that controls the fund, and (3) a separate management company that receives management fees (and sometimes houses employees, contracts, and operating expenses). From there, some managers consider more complex structures like master-feeder (to accommodate different investor types) or onshore/offshore components, which can introduce additional tax and regulatory considerations.

Align structure to strategy: a liquid, frequently traded strategy has different operational needs than a credit/venture/real assets strategy with long holding periods. Your structure should anticipate (among other things) valuation approach, liquidity/redemptions, gating/suspension mechanics, leverage and prime brokerage arrangements, and who signs trading and service-provider agreements. Separating the management company can also help isolate liabilities and keep fund economics clean.

Example: a founder forms a Delaware LP fund and a separate management company but routes expenses inconsistently and leaves authority provisions ambiguous. Counsel restructures the diagram so the GP has clear control, the management company properly earns management fees under a management agreement, and the fund documents match the intended economics and liability allocation.

So what should you do differently? Before fundraising, sketch a simple entity diagram (fund, GP/manager, management company, ownership) and confirm with counsel that it matches your strategy, investor profile, and how money will move.

Regulatory Landscape: Exemptions, Advisers Act, and Securities Rules

Most first-time hedge funds are built around a set of “stacked” exemptions — one for the fund (so it isn’t an investment company), one for the manager (so it may not need full SEC registration as an investment adviser yet), and one for the offering (so you can sell interests without registering the securities).

3(c)(1) vs. 3(c)(7): these are common Investment Company Act exclusions used by private funds. At a high level, 3(c)(1) funds limit the number of beneficial owners (commonly discussed as “100 or fewer”), while 3(c)(7) funds generally require all investors to be qualified purchasers. Your choice affects who you can admit, how you market, and how scalable the fund can be as you grow.

Advisers Act (manager registration): even if the fund is exempt, the manager may need to register — unless an exemption applies. One key exemption is the “private fund adviser exemption,” which can be available if you advise qualifying private funds and have less than $150 million in private fund assets under management (with specific definitions and calculation rules). See 17 CFR § 275.203(m)-1.

Securities offering rules (Reg D + Blue Sky): most funds sell interests via private placements under Regulation D (often Rule 506(b) or 506(c)), paired with required notice filings (Form D and state “Blue Sky” filings). These choices drive what you can say publicly, what investor verification is required, and your paperwork burden.

Example pitfall: a manager assumes every friend-and-family check is “accredited,” doesn’t collect proper investor questionnaires/support, and later discovers an investor doesn’t qualify for the chosen exemption. Fixes often involve subscription cleanup, eligibility gating going forward, and re-evaluating which exemption/structure fits the actual investor base.

So what should you do differently? Gate investor eligibility and registration decisions before you accept capital: decide 3(c)(1) vs 3(c)(7), pick your Reg D pathway, and confirm whether you’ll be an exempt reporting adviser or need registration based on your facts and growth plan.

Core Fund Documents: What to Draft, Key Clauses, and Risks

Private fund fundraising is paperwork-heavy for a reason: your documents are where exemptions, economics, and investor expectations get “locked in.” The goal isn’t to produce the longest documents — it’s to produce documents that accurately describe how the fund works, allocate risk clearly, and stay consistent across the stack.

- PPM (Private Placement Memorandum): describes strategy, terms, key risks, conflicts, fees/expenses, and operational mechanics. The core risk is mismatch: marketing language that promises one thing while the governing documents allow another.

- LPA or Operating Agreement: the rulebook — governance, capital accounts and allocations, withdrawal/redemption mechanics, gates/suspensions, transfers, key person/change of control, and limitation of liability/indemnification.

- Subscription Agreement: investor representations (accredited/QP status), eligibility, delivery items, and regulatory acknowledgments; often paired with AML/KYC information requests.

- Management/Advisory Agreement: documents the relationship between the fund and the manager — scope of services, management fee, expense allocations, standard of care, and conflicts handling.

- Side letters: tailored terms for specific investors (e.g., fee breaks, reporting, excuse rights). The big risk is creating inconsistent rights or MFN obligations that silently expand to other investors.

Clauses to tighten early: (1) expense and fee allocation (who pays what, and when), (2) liquidity terms (withdrawals, gates, suspensions), (3) conflicts/related-party transactions, (4) indemnification and limitation of liability, and (5) transfer restrictions and investor eligibility language. Drafting pitfalls usually come from generic templates that don’t match the actual strategy, service-provider setup, or investor profile.

So what should you do differently? Start with counsel-driven templates and tailor them to your structure and offering approach — don’t “DIY” the core documents and hope they’ll be clean enough to survive diligence later.

Onboarding, Compliance, and Actionable Next Steps

Once your structure and documents are in place, the day-to-day risk shifts from “formation” to execution. Most problems come from admitting investors inconsistently, missing filings, or operating without basic policies that institutional investors expect.

Investor onboarding: build a repeatable intake process that (i) confirms investor eligibility (accredited investor / qualified purchaser as applicable), (ii) collects KYC/AML information, and (iii) ensures subscription documents are complete before accepting funds. For most private offerings, you’ll also coordinate Form D and state notice (“Blue Sky”) filings, plus a calendar for ongoing reporting commitments you make to investors.

Compliance workflows: even exempt managers benefit from a lightweight compliance program. At minimum, document trading authority and controls, valuation approach (especially for illiquid positions), personal trading/code of ethics expectations, expense allocation procedures, and recordkeeping. These policies also make audits and administrator relationships smoother.

- Formation checklist: entity formation, governing agreements, management agreement, bank/broker/admin setup.

- Offering & filings checklist: Reg D pathway, Form D and state filings, marketing/communications guardrails.

- Onboarding checklist: investor questionnaire, subscription package, KYC/AML items, capital call/wire instructions.

- Governance & audit checklist: annual consents, valuation memos, side letter tracking, investor reporting archive.

Actionable next steps: set a 30/60/90-day formation plan with decision points (3(c)(1) vs 3(c)(7), 506(b) vs 506(c), adviser registration/exemption posture), then have counsel review the structure, offering process, and first closing checklist before you accept any subscriptions. If you’re evaluating when to bring in a lawyer, see hedge fund lawyer: what they do and when to hire one.

So what should you do differently? Treat compliance as a project plan, not an afterthought: document the workflow, assign an owner, and require a formal legal review before any fundraising begins.